Baubles, brooches & beads

We wear jewellery as articles of dress and fashion and for sentimental reasons – as tokens of love, as symbols of mourning, as souvenirs of travel.

Across our collections we find jewellery bought and worn for all these reasons, including an Irish parure composed of Irish harps and shamrocks from Rouse Hill House, a gold ring set with ruby and pearls from Vaucluse House, a cloisonné enamel brooch from Meroogal and a brooch found in the archaeology of Hyde Park Barracks. Also from the archaeology is a fragmented set of blue glass beads, not jewellery but a rosary.

Bessie Buchanan’s Irish parure Bessie Buchanan’s medallion necklace Bessie Rouse’s star and crescent moon brooch Elizabeth Buchanan’s buckle and strap bracelets Elizabeth Buchanan’s jet beads Elizabeth Buchanan’s mourning Brooch Hannah Rouse’s cameo ring Hannah Rouse’s onyx brooch Helen Macgregor’s brooch Jessie Thorburn’s brooch Kathleen Rouse’s scarab necklace Maggie Macgregor’s shell necklace Margaret Catchpole’s ring Rosary beads Woman’s brooch

Bessie Buchanan’s Irish parure

This matching set of earrings, brooch and necklace composed of Irish harps and shamrocks might be said to form a parure. It belonged to Bessie Rouse, nee Buchanan (1843-1924) who was born in Sydney to Irish-born parents. It may have been purchased in Dublin in 1867-1868 when Bessie and her parents made an extended visit to relatives in Ireland. Each piece in the set is made from Irish bog oak set in gold (possibly Wicklow gold). Although black jewellery was commonly worn during mourning, particularly in the years following the death of Prince Albert in 1861, it was also highly fashionable and worn for its beauty and sentiment. Bessie undoubtedly wore this jewellery in homage to her Irish ancestry. A photograph, which might also be a souvenir of the Buchanan’s visit to Ireland in the late 1860s, shows Bessie wearing the brooch and earrings from this set, with additional harp pendants attached to the earrings. The photograph, hand-coloured using the crystoleum process, depicts a radiantly red-haired young woman, dressed in green.

Bessie Buchanan’s medallion necklace

This necklace of graduated jet links is hung with a central pendant medallion and two smaller supporting medallions, all depicting the Roman goddess Minerva, goddess of wisdom. The smaller medallions may have once been detachable so that they could be worn as earrings. Jet was often worn as mourning jewellery in the nineteenth century but it was fashionable as well, particularly in the early 1870s. It was also light, so that substantial pieces of jewellery like this necklace could be worn without discomfort. The necklace features prominently in a pencil portrait of Bessie Buchanan (1843-1924) drawn by her friend Antoinette (Netta) Hayden in May 1872. Bessie and her parents William and Elizabeth Buchanan were then living at St John’s Terrace, Darlinghurst and Bessie’s friend Netta lived across the road. Her father was the Reverend Thomas Hayden, the rector of St John’s Darlinghurst. He had been born in northern Ireland where his father was the Archdeacon of Londonderry. Bessie’s mother Elizabeth Buchanan was also a native of Londonderry. It was the Reverend Thomas Hayden who officiated at the marriage of Bessie Buchanan and Edwin Stephen Rouse at St. John’s in March 1874.

Bessie Rouse’s star and crescent moon brooch

This romantic gold bar brooch, featuring pearl-studded stars and a pearl-studded crescent moon, was a gift from Edwin Stephen Rouse (1849-1931) to his fashionable wife Eliza Ann ‘Bessie’ Rouse (1843-1924) for Christmas 1886. Edwin Stephen bought the brooch on Christmas Eve 1886 from Hardy Brothers, goldsmiths and jewellers of Hunter Street, Sydney. In Victorian times seed pearls could symbolise tears when used in mourning jewellery but pearls could also be used to convey a personal message celebrating love. Edwin and Bessie has been married for 12 years in 1886 and had two young daughters, Nina born in 1875 and Kathleen born in 1878. A portrait of Bessie by Sydney photographers Freeman & Co shows her wearing the brooch attached to a black velvet choker and dressed in stylish evening attire with a black bodice festooned in net. Bessie’s father William Buchanan had died in March 1885 so perhaps the dress, and the brooch on the choker, are examples of the elegant reticence that black costume could represent for a woman of Bessie’s age.

Elizabeth Buchanan’s buckle and strap bracelets

This pair of Victorian bracelets, of jet and applied gold, was probably made in the North Yorkshire seaside town of Whitby, the centre of a booming industry turning and carving jet ornaments and jewellery in the nineteenth century. Each bracelet is constructed of rectangular jet tiles threaded onto double elastic strands and attached to a large centre medallion with a scalloped edge. In the Victorian language of jewellery the buckle signified loyalty, virtue, strength and protection. This meaning might be considered well-matched to the nature of their owner Elizabeth Buchanan (c1822-1890), loyal and loving wife of William Buchanan (c1799-1885). Elizabeth was remembered at her death for her kind and sympathetic nature and the sweetness of her disposition. The bracelets might have been purchased during a Buchanan family trip to Ireland, Scotland and London in 1867-1869. Elizabeth is wearing them – perhaps even displaying them – in a studio portrait by Sydney photographer William Bradley, probably taken soon after the family’s return to Sydney. When Elizabeth died in 1890 her daughter Bessie Rouse inherited her jewellery. She kept them in a red leather jewellery case at Rouse Hill House, where they remain.

Elizabeth Buchanan’s jet beads

This necklace of faceted beads is made of French ‘jet’, cast black glass made in imitation of organic jet, a fossilised wood. Jet jewellery, produced mainly in workshops in the North Yorkshire seaside town of Whitby, became immensely fashionable for mourning wear during the reign of Queen Victoria. French ‘jet’, heavier than Whitby jet, is more vulnerable to fracture and some of the beads in this necklace are cracked. It belonged to Elizabeth Buchanan, nee Lucas (c1822-1890) who had arrived in Sydney from northern Ireland in 1838. In 1842 she married William Buchanan (c1799-1885) who had come to New South Wales from Ireland twenty years earlier and had established a career for himself first as a civil servant, then as a surveyor and later a pastoralist. He died at his home Lara in Darlinghurst in 1885. A Freeman & Co studio photograph of Elizabeth taken in the late 1880s shows her wearing the necklace. After her own death in July 1890 it went to her daughter Bessie Rouse of Rouse Hill House. The elegance of the necklace with its deep black lustre could be worn by Bessie both in memory of her mother and as a stylish accoutrement.

Elizabeth Buchanan’s mourning Brooch

This jet mourning brooch, 5.6 cm in length, with a central rose motif finely carved in high relief, features in a series of photographs of the widowed Elizabeth Buchanan, nee Lucas (c1822-1890) taken by Sydney photographers Freeman & Co, probably not long after the death of her husband William Buchanan (c1799-1885) in March 1885. In one head-and-shoulders half-profile Elizabeth wears the brooch to secure her crape collar and also wears a small white widow’s cap, with train, very much in the manner of Queen Victoria. The photograph is the source for an enlarged hand-coloured version of the image on milk glass - an opalotype – that has been set in a plush red velvet mount and framed as a memorial to Elizabeth herself who died only five years after her husband, in July 1890. It was probably William and Elizabeth’s only child, their daughter Bessie Rouse of Rouse Hill House, who commissioned the opalotype which now hangs in the dining room at Rouse Hill House. It was certainly Bessie who inherited the brooch on her dear mother’s death.

Hannah Rouse’s cameo ring

This cameo ring is probably a travel souvenir. It belonged to Hannah Terry Rouse (1819-1907), the widow of Edwin Rouse (1806-1862) of Rouse Hill House and it is likely that she bought it during her ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe in 1868-1869, when she was accompanied by two of her daughters and her younger son, Edwin Stephen Rouse. Hannah owned a copy of John Murray’s Handbook to Rome and its Environs which she bought while staying at the Hotel d’Angleterre in Rome in February 1869. This guidebook provided advice on where to buy antiquities, mosaics and cameos. Cameo jewellery was a fashionable memento of a trip to Italy and immensely popular during the reign of Queen Victoria. They often depicted subjects drawn from ancient Rome, such subjects being thought to connote the wearer’s connoisseurship, taste, and classical learning. Hannah’s ring features a profile of the Roman Emperor Augustus. It is made of moulded white glass adhered to a dark glass ground and is set in a twisted gold rope frame. Hannah is wearing it in a photograph taken in the studio of London photographers Elliott & Fry, perhaps taken shortly before her return to Australia.

Hannah Rouse’s onyx brooch

There are several mysteries about this elegant enamelled gold brooch, beginning with its date and original owner. It is believed to have belonged to Hannah Terry Rouse, nee Hipkins (1819-1907) of Rouse Hill House, and to have been acquired following the death of her husband Edwin Rouse in 1862. The brooch, 2.5cm in diameter, certainly has the appearance of a mourning brooch, with a central onyx encircled with a band of black enamel set with seed pearls, denoting tears. The pearls are also ‘colourless’ and therefore appropriate for mourning but the onyx is polished to reveal a narrow band of white in the black and the combination of white and black was fashionable in Victorian times, representing a form of elegant reticence for married women of a certain age. Mourning brooches of this kind would usually have a glass back containing a lock of the loved one’s hair. There is no such compartment on this brooch but there is evidence that the back has been remade and the safety pin is definitely a later addition. Perhaps the original back was replaced because the glass had broken?

Helen Macgregor’s brooch

This small cloisonné enamel brooch, 4cm long, belonged to Mary Helen Grace (Helen) Macgregor (1881-1973), one of five daughters of Roderick Macgregor and his wife Mary Susan Thorburn. Helen was born in Cambewarra in the Shoalhaven district of New South Wales where her father was the local schoolmaster. She had the opportunity of a high-school education, winning prizes at Madame Wallrabe’s Nowra High School in 1892, and then went on to train as a nurse at the Coast Hospital, Sydney. Helen did not marry, although she had suitors, and chose instead to pursue a career as a private nurse. In 1919 she was involved in converting Nowra Public School into a temporary hospital to care for victims of the pneumonic influenza epidemic. Some years later she moved into the Thorburn family home Meroogal in Nowra, helping to care for her aging Thorburn aunts. Helen and her sisters Margaret Steel and Elgin Macgregor inherited Meroogal after their Aunt Tot Thorburn’s death in 1956 and Helen lived there until shortly before her own death in 1973.

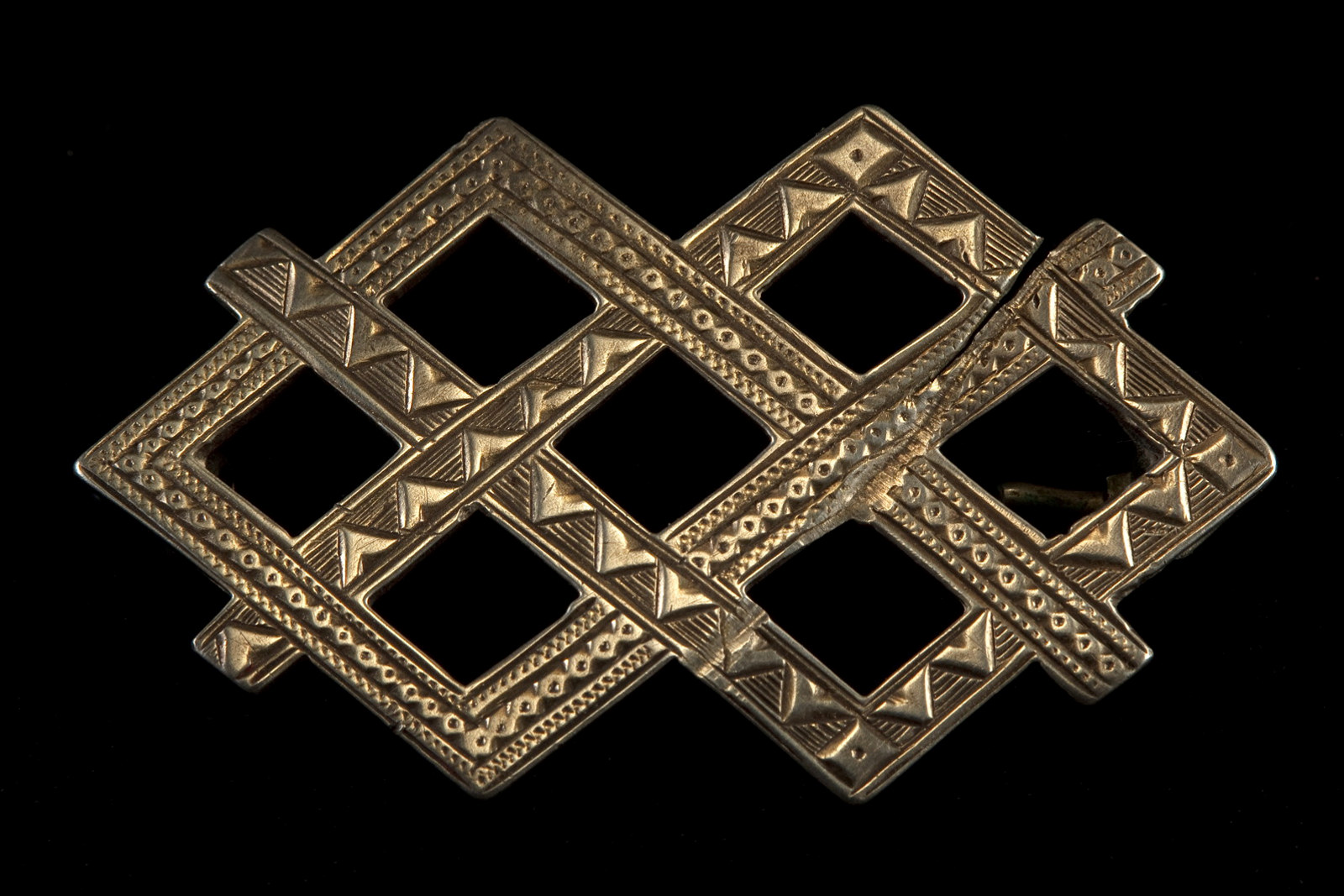

Jessie Thorburn’s brooch

This modest nickel silver brooch, 4.7 cm long, belonged to Jessie Thorburn, nee McKenzie (1824-1916) and later to her granddaughter Elgin Thorburn Macgregor (1890-1977). Jessie was born in the parish of Lochbroom, Ross Shire, on the north-west coast of Scotland, one of eight children of Thomas and Mary McKenzie. She left Scotland with her family in 1838, bound for Australia. The McKenzies settled in the Shoalhaven district on the south coast of New South Wales where, in 1846, Jessie married a Scottish-born farmer named Robert Thorburn. Like her own mother, she had eight children but was widowed in 1869 when her youngest child was only four years old. In 1886 Jessie moved with her unmarried daughters from the family farm Barr Hill, near Jaspers Brush, to the newly-built house Meroogal in Nowra. Jessie liked to wear brooches to secure her collars and is shown wearing this brooch in a photograph taken around 1890. It may be Scottish – more elaborate versions of this chased, lattice-work design can be found inset with agates and Scottish cairngorms.

Kathleen Rouse’s scarab necklace

This Egyptian-inspired necklace is in the form of a long serpentine silver rope chain set with turquoise glass scarabs and faux pearls. It belonged to Kathleen Buchanan Rouse (1878-1932), the second of two daughters born to Bessie Rouse (nee Buchanan) and Edwin Stephen Rouse of Rouse Hill House. Kathleen was a sophisticated and intelligent young woman, keen to escape the tedium of rural life on the outskirts of Sydney. She was an adventurous traveller, spending 18 months travelling through Europe in 1908-1909, often buying jewellery, clothing and trinkets for herself and her family. Her letters home included frequent reports on the beautiful garments and accessories for sale in great cities like Paris. This necklace was probably made in France and dates to the early twentieth century. Celebrated Egyptian tombs which had been opened and ransacked in the late nineteenth century provided inspiration for many early twentieth century jewellery designers. The scarab, a common amulet in ancient Egypt, was particularly fashionable and undoubtedly attracted the keen eye of Kathleen.

Maggie Macgregor’s shell necklace

Margaret Ross (Maggie) Macgregor (1888-1971) was about eleven years old when she was photographed in a pretty dress with a lace collar and wearing a shell necklace [M86/146). Maggie was the fourth daughter of Roderick Macgregor and his wife Mary Susan Thorburn of Torrisdale, Cambawarra, in the Shoalhaven district of New South Wales, but her necklace probably came from Tasmania. Tasmanian shell necklaces are very distinctive. They are usually made from maireener shells - Phasianotrochus irisodontes (rainbow kelp shell) or Phasianotrochus apicinus (pink-tipped kelp shell), found on the east and north coasts of Tasmania and the Bass Strait islands. Shell necklaces of this kind are an important part of the cultural heritage of Tasmanian Aboriginal (Palawa) women and have been made by Palawa women for generations. But in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century there was also a non-indigenous trade and manufacture of maireener shell necklaces, sometimes sold as ‘Hobart necklaces’, and Maggie’s shell necklace may be one of these.

Margaret Catchpole’s ring

This gold ring with garnet and pearl setting was once owned by Miss Jane Piper [1831-1905] daughter of Captain John Piper, military officer, public servant and landowner in colonial New South Wales. From the late 1820s the Piper family lived near Bathurst where Mrs Piper and her daughters ran a dairy farm - in her later years Jane Piper was as proud of her cheese-making as having been the first to introduce the polka to Bathurst. She was also keenly interested in early Australian history and believed that this ring had belonged to well-known convict Margaret Catchpole (1762-1819) whose life story has provided the source for a number of 19th century plays and publications and even an early Australian silent film. Miss Piper gave the ring to Mrs Harriett Eliza Stewart of Mount Pleasant, near Bathurst. On Mrs Stewart’s death in 1922 the ring went to her daughter Mrs Anne Athol Hughes (1864-1958), who later displayed it in her private museum in Hove, Sussex, labelled as Margaret Catchpole’s ring.

Rosary beads

This fragmented rosary of cobalt blue and clear glass beads was found by archaeologists under the floorboards on level 3 of Hyde Park Barracks, just under a dormitory window that once had a view out to St Mary’s Cathedral. The rosary can be dated to the period 1862-1886 when the Hyde Park Asylum occupied the top floor of the Barracks. The Asylum provided shelter for aged, ill and destitute women and also provided regular religious instruction. Visiting clergymen brought bibles and religious tracts, and perhaps even rosary beads. The archaeological evidence suggests that Catholic women were segregated from Protestants, the Catholic women occupying the southern dormitories while the Protestant women lived in the northern dormitory. This rosary would have originally had a crucifix attached, where the holder would begin the prayers, the fingers moving along the beads as the prayers devoted to the Virgin Mary are recited. The Asylum women had very few possessions, so this rosary must have been important to its Catholic owner, who we can almost picture standing at the window looking out to St Mary’s Cathedral while holding these beads. One wonders, what was she hoping for in her prayers?

Woman’s brooch

This delicate little metal brooch, only 2.5 cm wide, with three magenta-coloured faceted stones, must certainly have once been someone’s prized possession. Archaeologists found it at Hyde Park Barracks, beneath the floorboards below the corner window of the northern dormitory room on level 3. All the underfloor spaces contained masses of accumulated rubbish and lost treasures that had been hidden, fallen through the cracks, or stolen and packed into nests by the building’s colony of rats. Being slightly too large to have slipped through the cracks, this brooch was probably hidden deliberately beneath a floorboard for safekeeping. But by whom? Was it one of the young immigrant women who lived in the building from 1848, newly arrived by ship to begin a new life in the colony? Or was it one of the inmates of the Hyde Park Asylum, a government institution that cared for aged, ill and destitute women from 1862 until 1886. The Asylum women had few possessions. Was it her only remaining treasure? And why didn’t she eventually retrieve it from its hiding place beneath the floorboards?

Related

Published on