Murphy

Aboriginal man, convicted 1839

‘Murphy’ was one of a few Aboriginal men who tragically found themselves trapped in the British convict system.

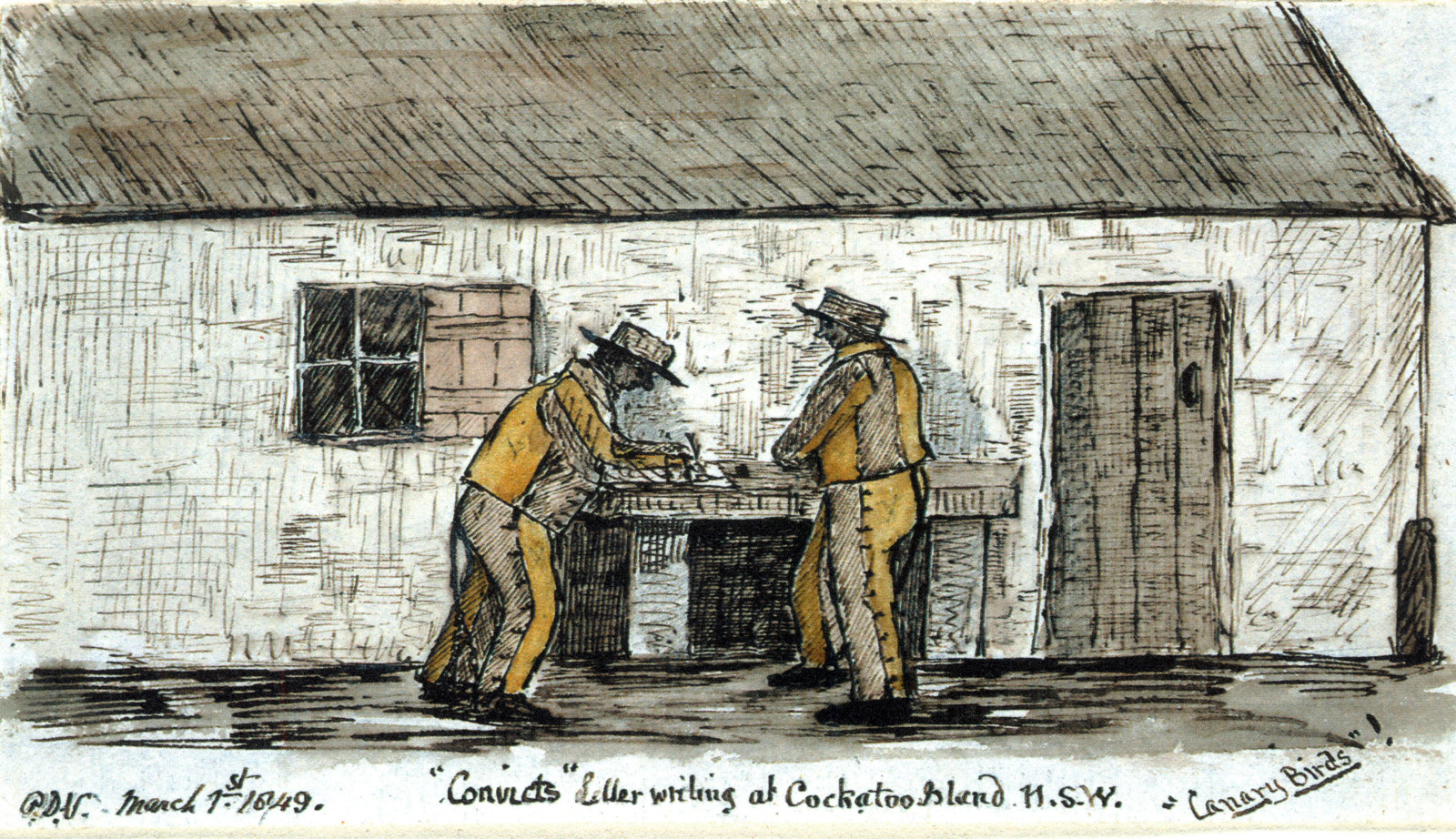

After being charged with highway robbery at Maitland in 1839, ‘Murphy’ was sent to cut sandstone on Cockatoo Island. When his sentence expired in February 1843, he was transferred to Hyde Park Barracks before returning home to Maitland. Three years later Murphy was once again arrested, described as ‘a rogue and vagabond’ and sent back to Cockatoo Island. In 1852 he was sentenced to 12-months’ hard labour at Parramatta Gaol, before spending the rest of his life behind bars.

Watch the video below of Dr Kristyn Harman discussing Murphy.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, an Aboriginal man known to Maitland colonists as Murphy survived multiple custodial sentences.

He was initially sentenced to transportation at the Maitland Quarter Sessions in December 1839, a sentencing that proved controversial. Murphy and another man were part of a group who attacked the settler Cottrell with waddies and spears and took the man’s jacket as he was travelling from Maitland to Morpeth. Their actions were considered by the colonists to have constituted highway robbery. At law, there were three distinct types of such robberies with different levels of punishment. The worst involved ‘wounding with a sharp instrument’ and incurred the death penalty. However, Murphy and his companion were charged with assaulting and robbing Cottrell. On being found guilty, they were sentenced to transportation.1

The Sydney Herald pointed out how in the attack on Cottrell ‘there was a spear used, and evidently an attempt to murder’ (that is, a sharp instrument), arguing that the charged laid ‘instead of rendering them liable to capital punishment, reduces it [the punishment] to transportation’. This, the newspaper reported, was not consistent with the principle of ‘“equal justice to blacks and whites”’. The Sydney Herald further argued that in the interests of equal justice the two Aboriginal men ought to ‘be sent out of the colony’ for one had already served three years at Goat Island for spearing a white man while the other, Murphy, had served two years in Newcastle Gaol for stealing. Under similar circumstances, so the argument went, a white man would be transported elsewhere.2 As it turned out, both men were transported to Cockatoo Island at Port Jackson along with another Aboriginal convict. Murphy survived long enough to be released from custody when his sentence expired on 11 February 1843. He was sent to Hyde Park Barracks before being returned to Maitland.3

Later the same year, Murphy appeared at the October Quarter Sessions. He had been remanded in custody on a charge of stealing a black swan, but on 11 October 1843 was ‘discharged without being placed upon his trial’.4 Several years later, in May 1846, Murphy was committed for trial for stealing a fowl from Dr Sloan at West Maitland in the middle of the night. Sloan’s servant later alleged in court that many fowls had been going missing. Murphy was remanded in custody to be tried at the Maitland Quarter Sessions in October 1846.5 Once again, the Chairman of the Quarter Sessions discharged Murphy without his standing trial.6 By the time he was set free Murphy had already been in gaol for five months.

At the end of October 1846, Murphy, who was described by the local newspaper as ‘one of the native denizens of the Australian soil’, was once again in custody. This time, he had been arrested taking some bottles from the rear of the Settlers’ Arms. Rather than being sentenced for stealing, though, Murphy was sentenced before the police bench ‘under the Vagrant Act, to be confined and kept at hard labour for six months as a rogue and vagabond’.7 This marks a significant shift in the way in which Aboriginal people in outlying townships were policed, excluded from mainstream society, and sent into captivity. Contemporaneous with Murphy’s arrest, complaints proliferated in Maitland from white residents who were concerned about ‘pilfering and other annoyances perpetrated by the aborigines’.8 One such annoyance related to colonists’ perceptions about the conduct of Aboriginal people who frequented the town:

We have been frequently disgusted at the number of naked blacks strolling about the streets of Maitland, and we are glad to find that this outrage upon public decency has at length been taken notice of by the proper authorities. Orders have this week been issued to the constables to apprehend such of the blacks as are found in a state of nudity in the streets of the town, and place them in the lockup, afterwards to be dealt with by the bench of magistrates.9

The Maitland Mercury observed how he ‘received his sentence with the utmost resignation, having already visited Newcastle Gaol, Cockatoo Island, and several of the lockups, &c., in the colony’ The newspaper ignorantly suggested that Murphy had ‘no doubt discovered that the beef and bread of those establishments are better than the scanty and precarious diet of the bush’.10 What it failed to mention was the appallingly high death rate of Aboriginal men within the convict system.

Murphy survived his 1846 sentence of hard labour but imprisonment was taking a toll on his health. On Wednesday 1 July 1852, he was arrested and brought before the police bench charged with ‘stealing a bundle’.11 Referred to in the Maitland Mercury as ‘an aboriginal whose name has frequently figured in our police reports’, Murphywas accused of taking a bundle of clothing and groceries belonging to a man named Riley at a local inn.12 He was sentenced to twelve months hard labour and sent to Parramatta Gaol. On 13 May 1853, the visiting justice of the Gaol wrote to the Colonial Secretary about Murphy’s health. It was the medical officer’s opinion that Murphy’s health was such that ‘further confinement would be attended with danger’.13 An annotation in the margin of the letter made it clear that Murphy was to ‘be discharged when well enough’.14

It seems Murphy eventually regained his health as he was brought before the court again in October 1853 charged with assaulting Constable Richard Kerr. The police officer had confiscated a red handkerchief that Murphy was trying to sell for threepence. Kerr claimed to have been assaulted by Murphy who later ‘came up and seized him by the collar, and swung him round, and called him a thief for taking away his handkerchief’. Murphy was convicted of assault and cautioned. As he had already spent time in custody since the incident, Murphy was discharged and the handkerchief, not having been claimed by anybody else, was returned to him.15

Notes

- ‘Maitland’, Sydney Herald, 13 December 1839, 2.

- ‘Maitland’, Sydney Herald, 13 December 1839, 2.

- Visiting Magistrate H. H. Browne to the Colonial Secretary, 28 December 1850, 191/50 4/3379 with enclosure ‘A Return Shewing the Number of Aboriginal Natives who have been Received on Cockatoo Island from the 1st Of January 1839 to the 16th December 1850’ prepared by George Ormsby, Superintendent, 50/12485 4/3379, State Archives and Records New South Wales (SARNSW).

- ‘Maitland Quarter Sessions’, Maitland Mercury, 14 October 1843, 4.

- ‘Committal of an Aboriginal Native’, Maitland Mercury, 6 May 1846, 2.

- ‘Maitland Quarter Sessions’, Maitland Mercury, 14 October 1843, 4.

- ‘Aboriginal Thief’, Maitland Mercury, 31 October 1846, 2.

- ‘Aboriginal Thief’, Maitland Mercury, 31 October 1846, 2.

- Maitland Mercury, 7 October 1843, 3.

- ‘Aboriginal Thief’, Maitland Mercury, 31 October 1846, 2.

- Maitland Mercury, 7 July 1852, 2.

- Maitland Mercury, 7 July 1852, 2.

- Visiting Justice David Forbes to the Colonial Secretary, 13 May 1853, 53/4389 4/3198, SARNSW.

- Visiting Justice David Forbes to the Colonial Secretary, 13 May 1853, 53/4389 4/3198, SARNSW.

- ‘Assaults’, Maitland Mercury, 8 October 1853, 2.

Related

Convict Sydney

The turning tide

During these final years of convicts at the Hyde Park Barracks, the newly designated city of Sydney gained its first outlying suburbs and industrial zones

Published on

Convict Sydney

Browse all

Convict Sydney

Cat-o’-nine-tails

One of the most common forms of convict punishment was flogging (whipping) with a ‘cat-o’-nine-tails’

Convict Sydney

Port Arthur

A notorious penal station made up of more than 30 convict-built structures and substantial ruins located in evocative, largely uncleared bushland on the end of the Tasman Peninsula

Convict Sydney

Cockatoo Island

Cockatoo Island was an infamous island prison established in Sydney Harbour from 1839 to 1869 for reoffending convicts and hardened criminals

![[Portrait of a man in the dock]](https://images.mhnsw.au/fotoweb/embed/2024/07/4ed595c1a86540bbbd08e47579e9b51d.jpg)

Convict Sydney

Lawrence Kavanagh

Kavanagh’s courage and spirit led him into further crimes after arriving in Sydney – bushranging, escape and attempted robbery under arms, which saw him transported again, to Norfolk Island for 14 years in 1831