Sydney as it could have been

Unrealised Sydney examines postwar visions that remained on the drawing board. What can we take away from this exhibition?

Schemes that didn’t make it tell us much about the time of their conception: the economic drivers, political context, and social and environmental values. They can record government agendas, the aspirations of private developers, the dreams of architects and planners, and community attitudes. The complexity of a city’s design and development is revealed.

Unrealised projects challenge us to think about what might have been (for better or worse), ponder the consequences of what was built, and reflect on major development and design choices that confront us today. From its early development as a town on unceded First Nations land through its inexorable transformation into a metropolis, Sydney has accumulated countless stories of possible futures that never came to be.

We can identify many forces that stimulate visionary thinking, including economic restructuring, technological change, design trends, environmental crises and shifting community attitudes.

Sydney in the 1940s

The Unrealised Sydney exhibition revisits some of the major redevelopment schemes for central Sydney proposed in the first few decades after World War II. Most of these spoke to a shared set of values, including modernism, material progress, efficiency, mobility and master planning, not just piecemeal improvement.

From the mid-1940s, a hopeful ideology of postwar reconstruction promoted the need for and openness to change. Sydney’s built environment, in particular the central city, faced a host of challenges, from ageing infrastructure, traffic congestion, delayed construction and housing shortages to inequalities in the provision of community facilities, poor civic design and a failure to do justice to the harbour setting. While still largely couched in terms of the city’s standing in the British Empire, there was an awakening to the imperatives of national, regional and global competitiveness.

In the Cumberland County Council’s metropolitan planning scheme of 1948, the CBD and its immediate environs were designated the ‘county centre’, singled out for comprehensive but unspecified renewal to improve both the economic health and the ‘dignity and appearance’ of the city.

There was no shortage of suggestions for improvements from architects, artists, inventors, developers, students and the public. Architect-journalist Florence Taylor concocted numerous imaginative schemes for remaking prominent sites into slick spaces of urban efficiency. Most of her ideas went unfulfilled, but they helped forge a culture of optimistic foresight at the onset of an extended period of prosperity into the early 1970s that economists dubbed ‘the long boom’.

Many proposals had been canvassed before the war, and an informal redevelopment agenda was taking shape by the late 1940s. A Sunday Telegraph reporter captured many of these in a piece that saw him transported, Rip Van Winkle–like, a decade into the future. Whizzing around by helicopter-taxi, he sees the transformation of the ‘drab, squalid, dingy’ city. Shabby Circular Quay has been remade by a broad promenade, a new civic square appears at the top of Martin Place, Sydney Hospital has been banished to the suburbs, Hyde Park boasts an underground car park, the Town Hall is set within a large civic centre, and Woolloomooloo has been resumed for open space.1

Sydney hotspots

There was a consensus about the main sites in need of renewal, if not about the best way forward. The CBD itself was regarded as a priority, with Macquarie Street and Circular Quay considered somewhat down at heel. The recommendations of state government–appointed advisory committees for these precincts in the 1930s dominated official thinking well into the postwar years.

The major narrative for Macquarie Street was the dream of a brand-new parliament house on the coveted hospital site opposite Martin Place. Both high- and low-rise renewal schemes were explored in the 1960s.

The constraints for revamping Circular Quay were largely set in place in the interwar years with the plan for a city bypass atop an elevated railway station, over objections from professional groups and the public, one of many occasions when development plans provoked intense debate. The postwar dilemma was what to do about it.

By contrast, hundreds of entrants in the international design competition of 1956–57 for the Sydney Opera House had virtual carte blanche on a magnificent site. Miraculously, the best entry was chosen – but the winning scheme itself wasn’t comprehensively realised. What the Opera House did do was create an iconic benchmark for design excellence.

The redevelopment saga of East Circular Quay (ECQ) in the 1980s and 90s, which spawned its own array of varied proposals, was largely driven by the search for a design that respected the very presence of the Opera House. Out of that emerged an appreciation of the many considerations required to fully inform urban design decisions.

Neither the Opera House nor ECQ were the planning disasters that some commentators have claimed. The making of the Museum of Sydney was similarly a stop-start process involving numerous schemes across two decades, but also ultimately resulting in a quality outcome.

The Rocks and Woolloomooloo were the two most contested precincts of the late 1960s and 70s. Here, aesthetic ideals of heroic modernism came to the fore with visions of high-rise buildings on multi-level podiums creating traffic-free pedestrian plazas. These unrealised schemes would’ve obliterated the historic character of the predominantly residential settings from which they sprang. They became lightning rods for criticism that politicians, planners and developers were out of touch with public sentiment, which favoured a more human-scaled urbanism. The unprecedented community campaigns against these proposals, including union-imposed green bans on development, led to progressive new planning legislation that emphasised social and environmental factors.

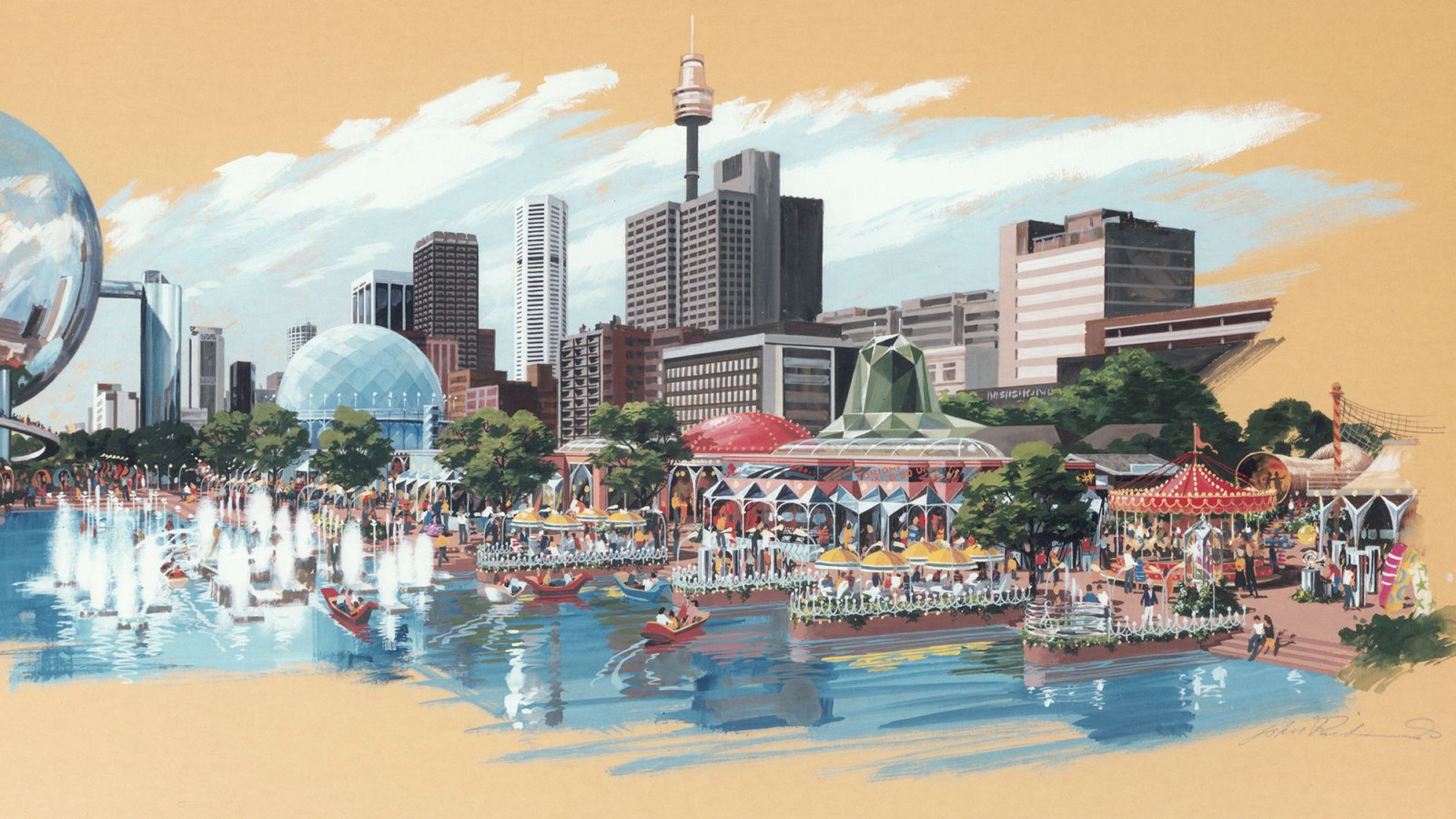

The revitalisation of Darling Harbour commenced in the late 1970s. It was then an obsolete maritime goods railway precinct largely under state government control, with no resident population to be displaced. The driving aspiration was to create a postmodern leisure and cultural enclave that would consolidate Sydney’s standing among major global cities. All manner of schemes were considered by the state government through invited submissions and unsolicited proposals. Community lobbying saved the early-20th-century Pyrmont Bridge from demolition but couldn’t prevent the loathed monorail (eventually closed in 2013).

A later project, East Darling Harbour (now known as Barangaroo), was also driven by the state government. The 2005 design competition was pitched at generating ideas rather than detailed proposals but a series of major modifications to the winning design resulted in a scheme significantly upscaled in commercial and design terms from that originally envisaged. Dogged by court cases and community concern at the quality of the public realm, the development ended up producing the CBD extension originally foreseen for Woolloomooloo nearly half a century earlier.

Lessons from history

Attempts to survey the unrealised city, including the range of visions presented in the exhibition, give us much to reflect upon: different expressions of the creative imagination, the societal context from which proposals emerge, power and authority in city governance, the vital role played by the community in determining the acceptability of change, and the overall contingent nature of city-shaping processes.

Although the focus of Unrealised Sydney is on a particular period and a limited geography, all the sites explored are ongoing stories. History and the need for community vigilance continues. The suitability, scale and impacts of new developments remain everyday issues not only in central Sydney but across the metropolitan area.

Note

Byron Blunden, ‘What Sydney may be like in 1957’, Sunday Telegraph, 27 July 1947, p11.

Related exhibition

Past exhibition

Unrealised Sydney

Unrealised Sydney presents a fascinating insight into the future of our city as it was imagined in the past

Published on

Related

First Nations

Do touch

We all know we can’t touch collection objects or artworks displayed in museums. However, the new display Cast in cast out by First Nations artist Dennis Golding at the Museum of Sydney includes a ‘do touch’ element

Excavating Australia’s first Government House

Did you know that when you walk into the Museum of Sydney, you’re walking over the remains of one of the most significant buildings in Australia’s history?

First Nations

Coomaditchie: The Art of Place

The works of the Coomaditchie artists speak of life in and around the settlement of Coomaditchie, its history, ecology and local Dreaming stories

![[First Government House, Sydney] / watercolour drawing by John Eyre](https://images.slm.com.au/fotoweb/embed/2022/11/8b76679c68c649dbb0ab45cfb954e5fb.jpg)

Museum stories

First encounters

The Museum of Sydney is built on and around a site that links us to the very beginnings of modern Australia