Ada Gallagher’s war

In 1914, at the outbreak of war, Ada (Adelaide) Gallagher was living with her husband, John, her daughter, Mary, usually known as Girlie, and her two younger sons, Fred and Frank, at 52 Gloucester Street in The Rocks.

The Gallaghers were part of a tight-knit working-class neighbourhood dominated by waterside workers and their families, and number 52 was one of a new block of 16 four-storey government-built ‘workmen’s dwellings’. John Gallagher was a coal lumper, loading and unloading the coal that powered steamships. For nearly 20 years he was employed in the bunkering operations of the Bellambi Coal Company.

All three of Ada and John’s sons enlisted in the First Australian Imperial Force. The eldest, Vinton, aged 21 and married with a young son of his own, was the first, joining up in August 1914. Frank signed up on 10 April 1915, aged 20, and his younger brother, Fred, joined up the next day. Fred, who was only 18, needed the written consent of his parents to join, and in his supporting letter John Gallagher wrote simply that his son was ‘anxious to go to the front on service’.

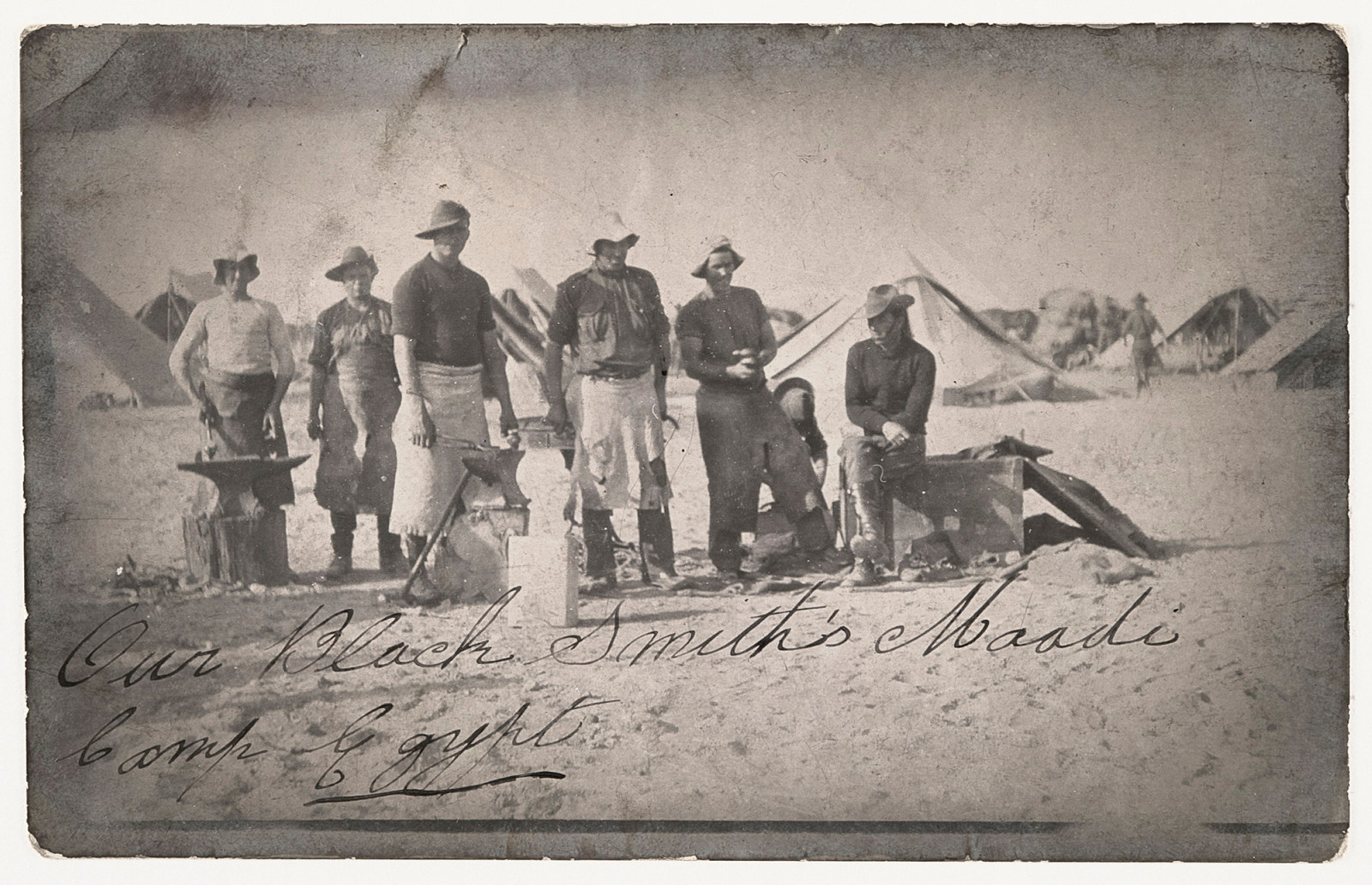

Over the course of the war the brothers kept in touch with home via postcards. These were short and sometimes hastily penned messages from battlefields, training camps and hospitals, some written on the back of photographs printed as postcards, others written on special World War I souvenir postcards. A note from Vinton sent from Egypt in February 1915 was written on the back of a photograph of Australian army blacksmiths at the Australian Light Horse camp at Maadi, not far from Cairo. Vinton was himself encamped at Mena, near the pyramids and the Great Sphinx of Giza.

Ada kept the cards in a special album, a practice known to her sons. In one undated card Frank asked his mother whether she had ‘been getting them other cards’, and added: ‘I have sent you a good few. I suppose you will have to get another album to put them in’. He had, he said, ‘only been out of the trenches a few days’ when he sent the cards.

Ada’s cherished postcard album, along with another album filled with family photographs, was passed down through three generations of the Gallagher family, and in 2010 was donated to Susannah Place Museum by Ada’s great-granddaughter Terri Williams.

Just a few lines to let you know …

With censorship rules that restricted what soldiers could write, the Gallagher postcards reveal little of the horrors of the war. Many of the cards begin with the familiar greeting ‘... just a few lines to let you know that I am alright and hope all at home are the same’. The brothers were keen for everyday news from home; in one card, Frank asked his father to send him newspaper cuttings of the boat race results. The brothers regularly reported whether or not they had heard from or seen each other, as well as when they ‘met other boys from the Rocks’, including one of the Curran boys, who lived next door at 54 Gloucester Street.

A number of postcards refer to a ‘strike’. This is likely to be the 1917 general strike that had begun in NSW with railway workers and spread to other unions, including waterside workers such as John Gallagher. The strike lasted for six weeks, from early August to mid-September, causing widespread hardship for the families of striking workers who had no wages coming in. On 5 November, Frank wrote to his father from France to say that he would be sending him five pounds as soon as he could; he also asked ‘what was the cause of that strike’ and ‘did they get what they wanted’. He thought that things must be tough on the waterfront, with fewer ships in port since the Orient Line Shipping Company had ‘chucked the mail service up’. The company’s ships had all been commandeered for war service.

In an interview recorded in 1992, John Gallagher’s grandson Leslie Gallagher (Vinton’s son) recalled that because of ‘the big 1917 strike’ John left the wharves and went to the railways.1 Sometime late in 1918, Ada, who also used postcards to keep in touch with her sons, wrote to Fred telling him that ‘dad is still in his job there is no coal work yet’.

Have you got any of them silk cards …

Like many other Australian soldiers in France, both Frank and Fred were much taken with a type of embroidered silk postcard produced during the war in great quantities as sentimental souvenirs. Ada’s album contains more than 130 silk cards. In one card sent to his mother, Frank asks: ‘have you got any of them silk cards well you ought to have some of them by now I have sent enough’. (Frank rarely bothered with punctuation.)

A family briefly reunited

In January 1916, six months after sustaining a bullet wound to his arm at Gallipoli, Fred arrived home at 52 Gloucester Street to recuperate. Five months later, Frank was sent home aboard a hospital ship for ‘3 months change’, having been diagnosed with ‘irritable heart’. We can only imagine how John, Ada and Girlie must have felt to have Frank and Fred home safe. However, their happiness was only brief. On 13 November 1916, Fred re-enlisted in the AIF. Three days later, Frank also re-enlisted. According to family history, Frank joined up again promising his mother that he would take care of his younger brother and bring him home.2 On 23 August 1918, Frank was killed on the Western Front. Almost a year later, Ada received Frank’s personal effects, including ‘cards, photos’ and ‘paper cuttings’. It seems likely that she put the ‘cards’ into her treasured album.

Fred and Vinton both survived the war.

Postscript

In 1932 Ada and John Gallagher moved from 52 Gloucester Street just a few houses up the road to number 58, now part of Susannah Place Museum. In 1937, Girlie, who always lived close to her parents, moved into 64 Gloucester Street (also part of Susannah Place Museum) with her second husband, Arnt Martinius (Martin) Andersen. When Ada and John passed away within weeks of each other in 1949, Girlie and Martin and their two sons moved into their old home at number 58.

Footnotes

- Oral history interview with Leslie and Florence Gallagher, 1992, Susannah Place Museum collection

- Conversation with Florence Gallagher, 2014.

Published on