Isabel Swann: the Women’s Peace Army & free speech

Isabel Frances Swann (1881–1961) was an ardent peace activist, an anti-conscription campaigner, defender of free speech and secretary of the NSW branch of the Women’s Peace Army.

She was the sixth of 11 children born to Quaker-bred schoolmaster William Swann and his wife, Elizabeth Devlin, and was brought up in a household influenced by the commitment of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) to oppose participation in war. Throughout World War I this household was centred on Elizabeth Farm at Parramatta, owned and occupied by the Swann family from 1904 until 1968.

Three of Isabel’s older sisters, Rebecca, Edith and Elizabeth, and her brother John were active in the affairs of the Religious Society of Friends from early adulthood. Her younger sisters Ruth and Nona joined the society at a later date.

In the 1890s Swann family members were also avid followers of the debates over women’s suffrage. Margaret Swann (1871–1963), the eldest of the sisters and a teacher, was elected president of the Granville branch of the Womanhood Suffrage League in March 1896. After women gained the vote in NSW in 1902, Margaret was active in the Parramatta Women’s Electoral Bee, an organisation formed to campaign around issues of particular interest to women voters. Rebecca Sharp Swann (1873–1959), the second of the sisters and also a teacher, joined the Women’s Political Educational League, established as a lobbying organisation to educate women in the use of their vote. She wrote a pamphlet for the League titled ‘Concerning your vote’, addressed to the women electors of NSW.

Anti-conscription

Rebecca Swann joined the NSW branch of the London Peace Society in 1899 following the outbreak of the Boer War. Her parents were also members of the society. Other members of the family, including Isabel Swann, were propelled into anti-war activism by the 1911 introduction of legislation for compulsory military training for boys aged 12 to 18. In 1912 both Rebecca and Isabel joined the newly formed ‘Australian Freedom League (for the abolition of the compulsory clauses of the Commonwealth Defence Act)’. Rebecca wrote a pamphlet for the league titled ‘Free citizenship or military tyranny?’ and on at least one occasion she bore witness at the Sydney Water Police Court when a number of young boys were summoned to appear before a Children’s Court charged with a breach of the Defence Act. In July 1913 a young cousin of the Swanns, a Quaker from Newcastle named Sidney Crosland, was prosecuted under the Act and sentenced to confinement in Victoria Barracks in Sydney.

Isabel Swann’s own anti-war involvement intensified once war was declared in 1914. Her associations became more radical when Prime Minister Billy Hughes announced his intention to introduce conscription in 1916. Hughes called a referendum on the issue for 28 October 1916, triggering a campaign around conscription that divided the nation. The electorate voted ‘No’ to conscription by a small majority in October 1916 but Hughes called another referendum for 20 December 1917.

In Sydney the pro- and anti-conscription arguments were aired before huge crowds every Sunday afternoon in the Domain. The radical journalist Mary Gilmore, writing for the ‘Women’s Page’ of the Australian Worker newspaper in the lead-up to the first referendum, dubbed the Domain the ‘People’s Open Air Palace’. She also observed that ‘Sydney women all seem to be politically alert these days’, judging by the presence of women at every street corner meeting and in the Domain and the large number of public meetings advertised specifically ‘for women’, both in the city and in the suburbs.

Isabel Swann was certainly active in both city and suburbs. She lived at Parramatta but worked in the city and was, like her sisters, an independent professional woman. She had trained as a dentist and was the first ‘lady surgeon dentist’ in Parramatta. Following her registration in July 1902, she established a practice in King Street, Sydney, later moving to Buckland Chambers in Liverpool Street.

The Women’s Peace Army

By 1917 Isabel was secretary of the NSW branch of the Women’s Peace Army (WPA), the most visible and influential of the women’s anti-conscription organisations, formed in 1915 under the leadership of Melbourne feminist and suffragist Vida Goldstein. Isabel was busy – she might chair a special women’s meeting in the Sydney suburb of Dulwich Hill on Friday night, conduct a regular meeting in Parramatta on Saturday night, together with Miss Eva Tuckwell from the Parramatta Labour League, and then speak on the Women’s Peace Army platform in the Domain on Sunday.

This was a pattern of activity that she maintained throughout 1917 and sustained even after the second conscription referendum, when the nation again voted ‘No’, this time with a larger majority.

Women’s Peace Army and Anti-Conscription League leaflets, 1916–17. Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW: F91/49

Her activism extended beyond the WPA to include involvement in the Australian Union of Democratic Control for the Avoidance of War, a group modelled on a leading British anti-war organisation. The British UDC was an early advocate for the League of Nations and argued for greater public control and scrutiny of national and international diplomacy. Isabel conducted a home study circle for peace activists using course materials produced by the UDC. She was also one of the chief organisers of an interstate peace conference initiated by the Australian UDC and held in Sydney in March 1918. And by mid-1918 she was deeply involved in a new campaign around free speech.

The free speech campaign

Throughout the war, newspapers operated under a censorship regime with which the mainstream press was mostly willingly compliant. The editors of three different labour movement newspapers, on the other hand, were charged under the War Precautions Act either for sedition or for uttering remarks prejudicial to recruiting. In 1916 a group of 12 members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the most radical of the anti-conscription organisations, had been tried and imprisoned on charges of sedition, arson and forgery, a trial seen by many as a political move to silence the organisation. In 1917 the IWW was declared an unlawful association. Isabel Swann offered her professional services as a dentist to the imprisoned IWW men.

Speakers in the Domain were kept under surveillance by plain-clothes police, and Isabel Swann’s presence on various platforms in the Domain was duly recorded. She was required to obtain permission from the State War Council for the WPA to sell The Woman Voter newspaper and a WPA ‘Peace’ button. Despite these constraints, the NSW branch of the WPA believed that the educational value of the meetings was ‘beyond estimate’, as people from all parts of the state could be found among the listening crowds. The Woman Voter reported in June 1918 that Isabel was indefatigable in her commitment to the cause: ‘In spite of the exactions of an arduous profession she turns up Sunday by Sunday, hail, rain, or shine, to deliver a message of true brotherhood, internationalism, and hope for the future’.

In August 1918 NSW Premier William Holman introduced the Sedition Bill, a controversial piece of legislation seeking to disenfranchise anyone convicted of sedition, especially Holman’s opponents in the Parliament. The WPA joined forces with the Social Democratic League, the Socialist Labour Party, the Industrial Labour Party and the Committee for the Release and Defence of the IWW Men, to form a Free Speech Committee. Isabel travelled to the south coast and then north to the Hunter to speak on behalf of this committee. She was billed as ‘one of Australia’s foremost lady orators’ in the advertisement for a meeting held in Newcastle in September 1918.

Holman’s Bill never became law, lapsing with the end of the war in November 1918. Sunday afternoon meetings in the Sydney Domain, on the other hand, continued for some time after the war, with speakers, including Isabel Swann, calling for a general amnesty for all those imprisoned for their opposition to conscription and war. The WPA remained active until late 1919, when it was incorporated into the Australian section of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Isabel Swann remained an activist for the rest of her life.

More

WW1

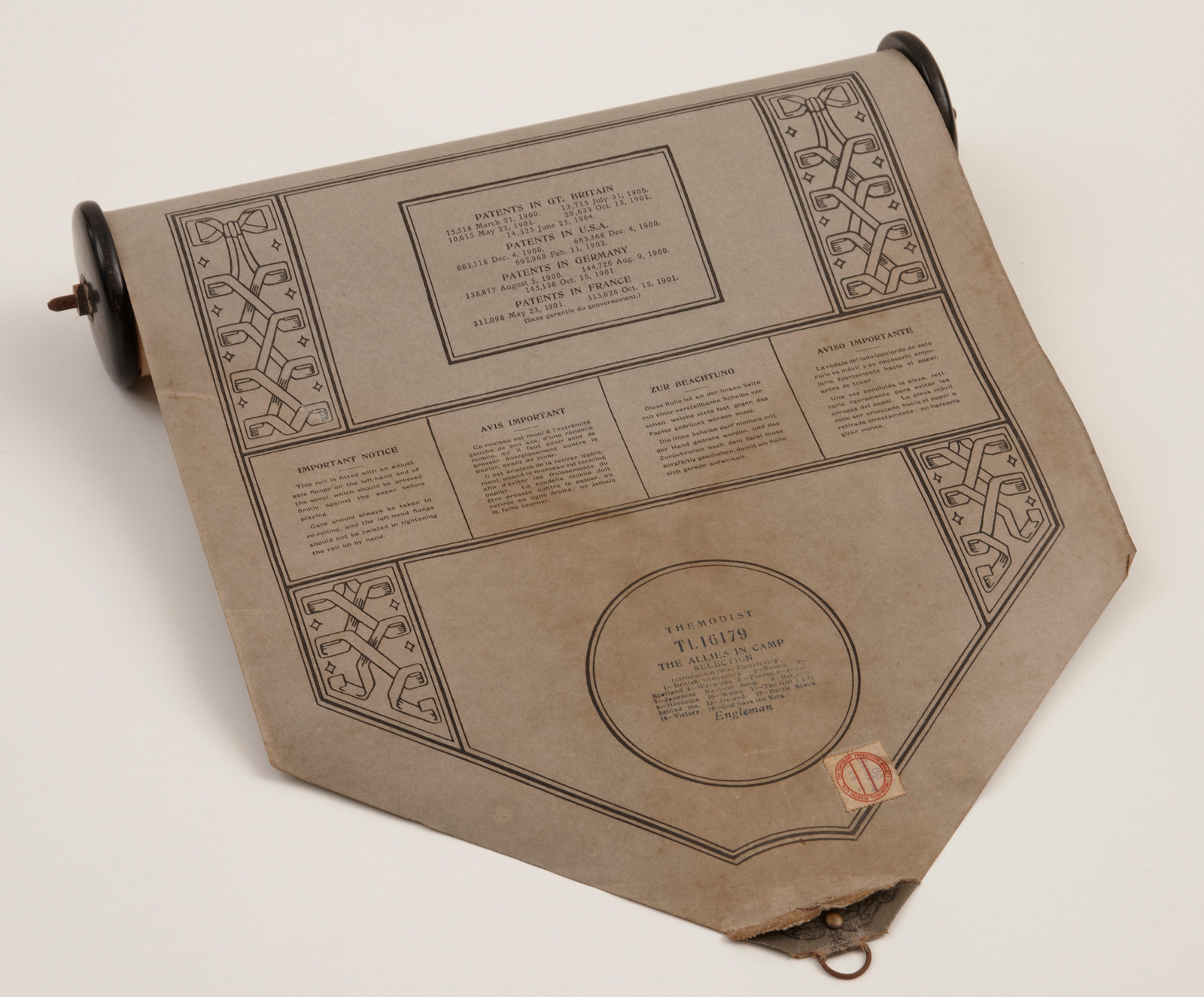

The Allies in camp music roll

Rouse Hill house boasts a fine pianola, a player piano, which came into the house just a few years before the outbreak of World War I

WW1

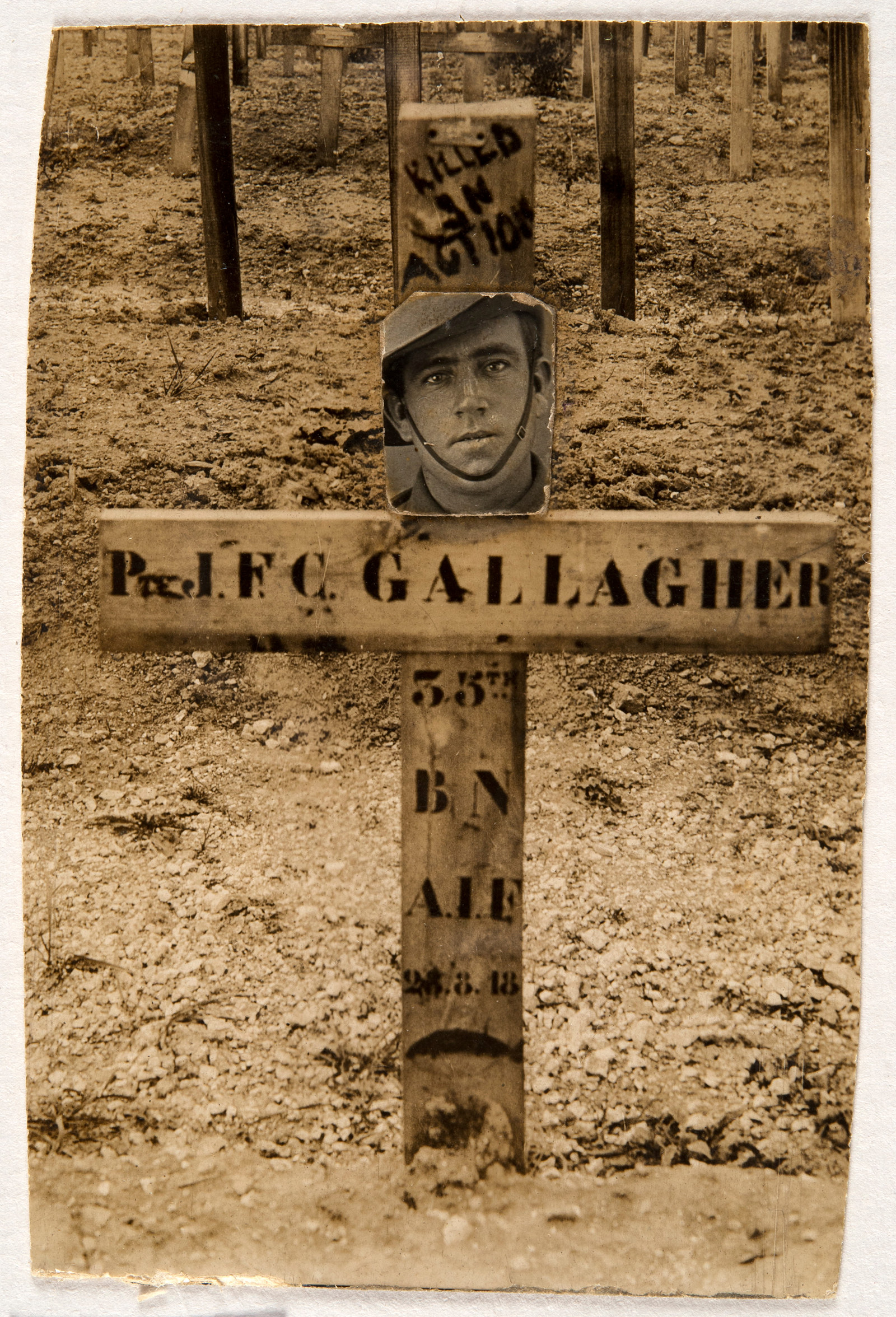

Frank Gallagher’s grave markers

Late in the afternoon on 23 August 1918, Private John Francis Cecil Gallagher, known as Frank, was killed by shellfire at 23 years of age

Published on