The archive’s negatives

The New South Wales Police Forensic Photography Archive contains photographic negatives in several formats and sizes created between around 1910 and 1964. These negatives are both a record of how New South Wales Police used photography and a reflection of how photographic technology changed during these decades.

In the black and white analogue photographic process, the negative can be considered an intermediary to the positive photograph. It is the source image used to print multiple identical prints. The negative has a supporting base layer that is coated with a light-sensitive silver gelatin emulsion. After exposure in camera and processing, the negative contains a monochromatic, tonally inverted image. The bright areas appear in blacks and the areas of deep shadow have no visual presence on the clear support layer. The archive comprises negatives that are manufactured, retail products (not handmade) and are a precursor to the black and white films still in use today.

The archive’s two main negative formats are dry glass plates and sheet film (probably nitrate or cellulose). The earlier negatives are dry plates, while sheet film is the primary format later in the collection. However, different formats and sizes were in use concurrently.

The negatives themselves reveal much about the photomechanical processes used by police. The range of negative formats is evidence that New South Wales Police employed a number of different cameras (and/or camera backs) for their photographic work and that these cameras were updated over the years.

After taking the photographs, police photographers chemically processed the negatives in a darkroom and printed them for use. Ultimately the photographic prints were pinned to case files and presented in court, alongside other evidence. The negatives were filed separately and could be reprinted if evidence was called into question or the case was revisited.

Once an investigation was complete, police photographers stored the processed negatives in the original cardboard boxes, stamped with identifying numbers, and, later, in paper envelopes with handwritten inscriptions. As the original indexes that once explained the content of the archive have been lost, these original enclosures give vital clues to help us understand the negatives, and provide information about the manufacturers, formats, sizes and emulsion speeds of the negatives used by police around the time the photographs were taken.

The negatives were much-handled working records, as evidenced by the marks, abrasions and fingerprints of policemen still visible today. Information about the suspect and image content has sometimes been written on the emulsion (reverse) side of the negatives in ink or pencil; this needed to be written back to front in order to appear the right way around on the printed photograph. Sometimes parts of the emulsion have been scratched, sketched or inked out by the photographer to obscure or conceal details originally captured in camera.

Deterioration is inherent to any photographic medium. A negative’s material, chemical processing (and its residue), handling, storage history (temperature and humidity) and age are all factors that could impact the state of preservation. The passing of time is evident where emulsion shimmers silver, is yellowing or has been completely washed away as a result of the flood that first brought the negatives to the attention of their police rescuers.

We repackage, register and identify the negatives prior to digitisation. Each negative is rehoused in its own archivally stable enclosure and stored alongside related negatives and the box or envelope they were found in, so the original archival order is retained. After the negatives are scanned, they are stored in a climate-controlled room with stable relative humidity and temperature to prolong their life.

Related

A popular nuisance – controlling the street photographers

By the mid-1930s the street photography ‘craze’ saw increasing numbers of photographers on Sydney’s streets – all competing for the best locations and the most promising marks

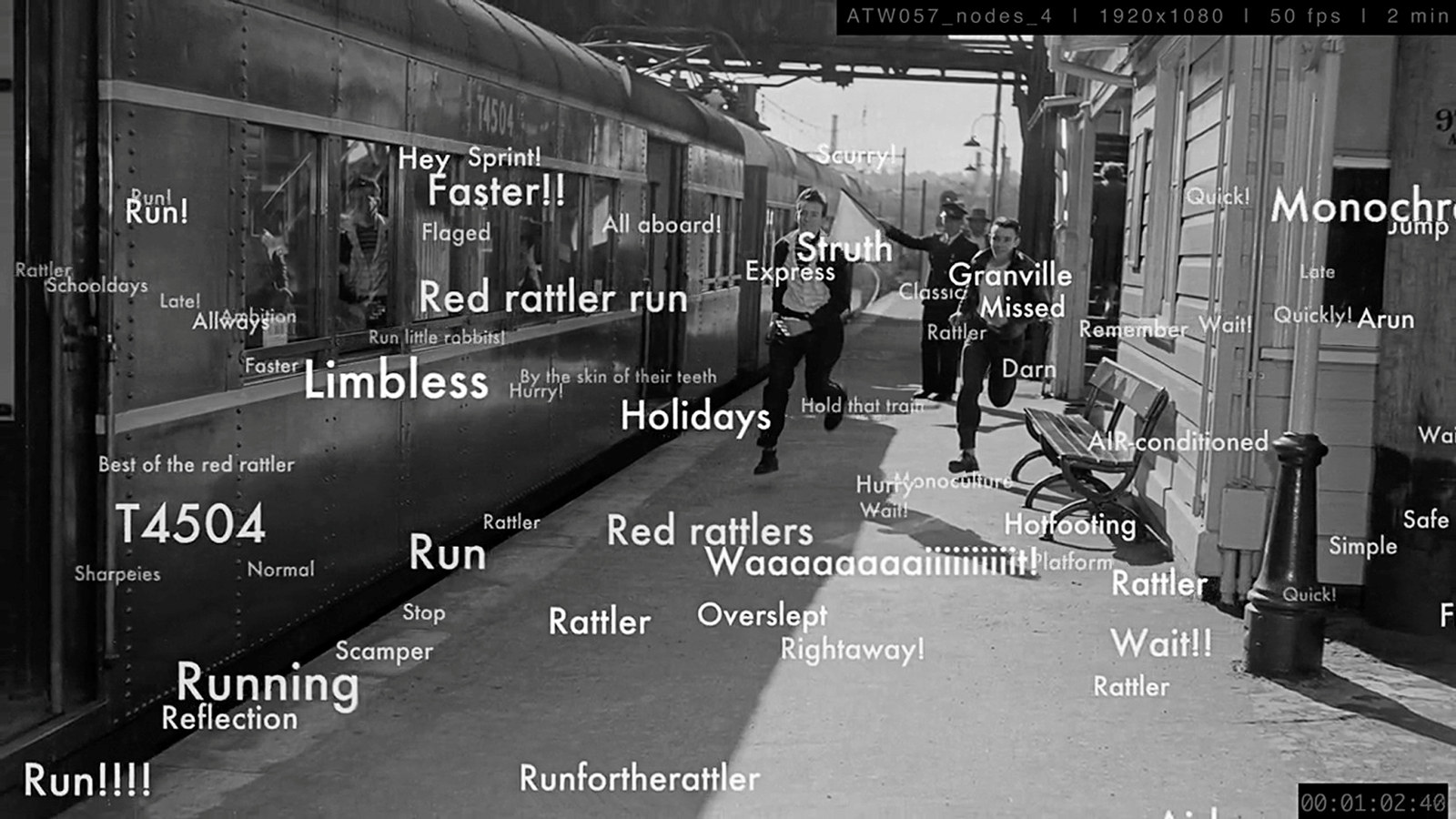

About the exhibition: A thousand words

An innovative new exhibition invites the public to become the curator, sharing their responses to historical photographs from two of Australia’s richest and most significant collections

Published on