Brushing up on our housekeeping

When you visit Rouse Hill House, you get the feeling that the house is preserved in a state of suspended animation, never changing, frozen in time. While this is part of the appeal of Rouse Hill House, it’s also quite misleading. In fact, there’s an on-going process of change taking place, and often there are associated challenges.

The conservation model we follow at Rouse Hill Estate is based on the concept of ‘conserve as found’. Many historic houses, including several managed by Museums of History NSW (MHNSW), aren’t ‘untouched’ in the way Rouse Hill House is – often they were heavily restored or curated in the past and we have worked to interpret them through documentary material and primary evidence. This has allowed us to reinstate elements in the houses, such as soft furnishings, based on archival or documentary evidence. For example, the recent refurbishment of the Drawing Room at Vaucluse House.

At Rouse Hill Estate, our approach is different due to the unique untouched nature of the property, so nothing is replaced, we simply maintain, and only conserve when absolutely necessary – that is, we attempt to sustain the house and collection as it looked following its acquisition by the NSW State Government in 1978 (the property was transferred to the Historic Houses Trust, now Museums of History NSW, in 1986). For this model to be sustainable, however, it requires a considerable amount of care and a thorough knowledge of the collection. Everything decays eventually, but with careful management, we can slow this process and preserve the collection for as long as possible.

In our roles as Assistant Curators within the House Museums Portfolio, Rebecca Jones and I spend a lot of our time getting to know the interiors of our houses. This is particularly important at Rouse Hill House. In fact, it’s part of the process of preventative conservation that we employ in the house. One of our key responsibilities is the day-to-day housekeeping, and it’s a lot more complex than you might think!

Know your dust

Basic housekeeping is the foundation of conservation cleaning, and underpins the way we care for our historic interiors. Believe it or not, dusting is one of the most important elements of our housekeeping routine. Dust, as it builds up on a surface, be it furniture or fabric, begins to absorb moisture, especially when the relative humidity (RH) is high (over 70%). As moisture is absorbed, the dust begins to adhere to the surface of the object, and becomes harder to remove – thus requiring more abrasive measures to remove it. It also becomes a source of food for mould and insects, which are another major issue for historic interiors, as they can cause damage to just about every material from fabric, to timber, to paper. In order to manage the dust, we work to a schedule to keep on top of the cleaning, checking each room in the house regularly. We get to know the collection, can recognise changes, and are able to identify and resolve issues quickly.

Galleries, museums, and occasionally even conserved historic houses have carefully controlled environments that enable curators to maintain a constant temperature and constant level of RH – conditions that are optimal for the long term survival of objects. At Rouse Hill Estate, we don’t have that luxury. We can’t seal the house, and we don’t want to. The pleasure of visiting Rouse Hill Estate is its immersive nature, that feeling of stepping into such a complex, layered history.

Ideally, we’d love to keep our interior conditions between 45% - 65% RH, with a temperature of about 22°C, however this is simply not possible at Rouse Hill Estate. The house undergoes major fluctuations of temperature and humidity throughout the year – much as it has done for the past two centuries. Our main methods of climate control are just the same as used by the Rouse and Terry family – closing windows and shutters during the heat of the day, and opening them when it is cool. Today many of the windows don’t seal tightly, doors may not close properly, and walls and ceilings may have cracks that allow dust ingress. While we do everything we can to minimise this, including door and window snakes and portable air scrubbers, frequent dusting remains an essential element in preventing deterioration to the collection. Keeping the building shut tight during a dusty, windy summer is essential, and the impact of the ’great dust storm’, which turned Sydney into a red Martian landscape a decade ago, and coated every object, floor wall and ceiling in the house is still burned into our curators’ minds!

Under rug swept

One of the most difficult elements of the collections to clean are the carpets and rugs. It’s also why we have visitors don booties when they enter the house; the difference this makes by simply preventing gravel and dirt from shoes from impacting on the interiors is considerable.

The scope of the collection at Rouse Hill House enables us to piece together how the Rouse family themselves cared for their carpets over time, and evocatively illustrates how technologies have changed; we see for instance a late 19th century carpet sweeper in the pantry, two mid 20th century electric-powered vacuum cleaners in the scullery, and another upstairs in a hallway. But in order to preserve the carpet for as long as possible, we now undertake a very low impact form of cleaning.

Careful testing demonstrated that any direct application of a modern vacuum cleaner to the historic carpets would pull out tufts of fabric, damaging the carpets further. Instead, we use a process known as brush vacuuming; with the vacuum set on its lowest setting, we hold the nozzle parallel to and slightly above the carpet, then use a brush to flick surface dust and debris from the pile toward the nozzle. While it may not give the carpets a ‘deep’ clean, it’s enough to maintain them, and removes the problematic surface dust. We use a vacuum with a HEPA filter (from ‘High Efficiency Particulate Air’) which captures especially fine particles. This minimises dust being blown out into the room again, as well as capturing fine particles of loose mould. In terms of frequency, we limit the carpet cleaning within the rooms to around twice a year – despite our care, there’s still some abrasion to the surface.

It’s a careful balancing act, to fulfil the aesthetic requirements of a house museum, and to maintain the conservation requirements of a fragile collection, but it’s worth getting it right to protect this significant place.

‘Conserve as found’ at Rouse Hill Estate

Rather than replacing old material with new, our approach at Rouse Hill Estate is to support as much of the built fabric as possible, to maintain the condition of the property as it was when it came to MHNSW. We also aim to minimise the impact of any works on the building.

Published on

Related

Browse all

A Gothic Angel

In the drawing room at Rouse Hill your eye is instantly drawn to a small painting on the far wall; a figure of an angel in a shining gilt frame, acquired in the 1870s.

Keeping cool

Shading the face, fanning a fire into a blaze or cooling food, shooing away insects, conveying social status, even passing discreet romantic messages - the use of the fan goes far beyond the creation of a breeze.

WW1

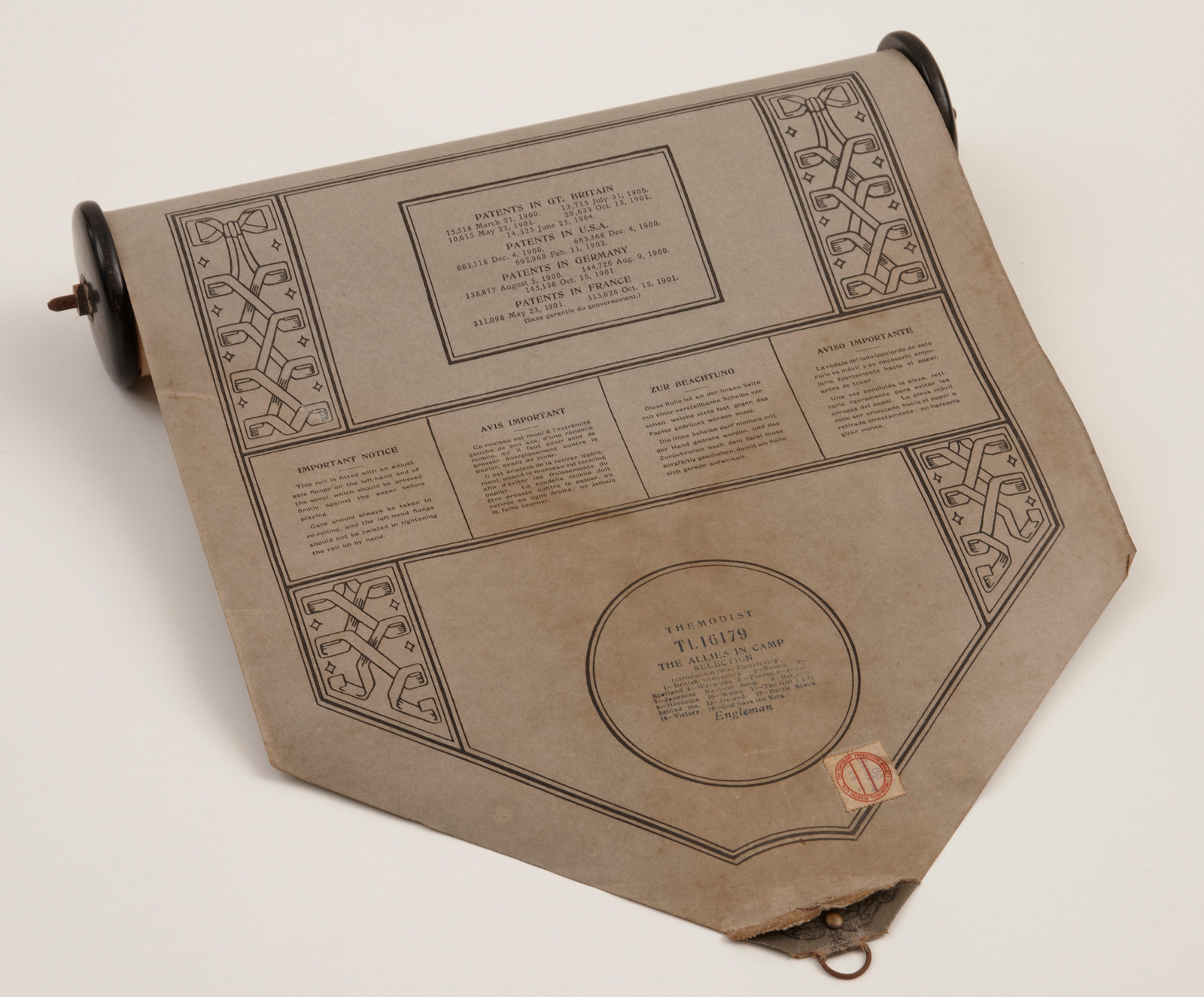

The Allies in camp music roll

Rouse Hill house boasts a fine pianola, a player piano, which came into the house just a few years before the outbreak of World War I

Baubles, brooches & beads

We wear jewellery as articles of dress and fashion and for sentimental reasons – as tokens of love, as symbols of mourning, as souvenirs of travel